On a recent trip to Washington, D.C., to participate in the Episcopal Church’s Reparations Summit, I ran into an old friend from my time at St. Mark’s Capitol Hill. We were in a conversation following a presentation on the impact of the Doctrine of Discovery and the “Christianization” of White male patriarchy, when I heard him share his story. He talked of his journey as a gay man in a world that conditioned him to be a straight, White, hetero-normative male. He said, “I spent the first half of my life as a straight, White man with a wife and children. And, then I woke up.” He was very clear, waking up to his identity as a gay man didn’t diminish the first half of life with his family any more than his family diminished his second half of life as a gay man in a loving, committed relationship. But now that he is awake, he cannot return to the way things were.

I can relate to my old friend. I, too, have woken up. I cannot unsee what I have seen about myself and the life I was born and bred for – that world I was conditioned and coded to protect, preserve, and prosper. I cannot go back to the way it was. I am awake now.

When my son, Hill was twelve years old, he asked me, “Daddy, what does my name mean?” I told him of how our family has a tradition of naming the eldest son after his father. I told him how I was named for my father as an eldest son and how my father, being the second-born, was named for his grandfather, a United States senator. And, he asked, “But Daddy, what does my name mean.” I started to tell him (but didn’t) that a man’s name tells the story of who he is and who he will become. After all, that is what I was told growing up. You see, I was taught the eldest son carries his father’s name, perfects his father’s profession, and improves his father’s reputation. The weight of a family’s social standing is saddled on a son’s shoulders, before he has even moved out of the house. My family had been in Montgomery, Alabama for eight generations, and among its patriarchs were lawyers, a federal judge, and a United States Senator. By the time I went graduated college, it had ingrained into me that I was to carry on the family legacy of law and politics. I was to protect and preserve the power and privilege that was my birthright, expand that power and privilege for my family, and raise my son to carry it forward for future generations.

But I am awake now. And I have chosen a different path. For myself; for my son; for my family.

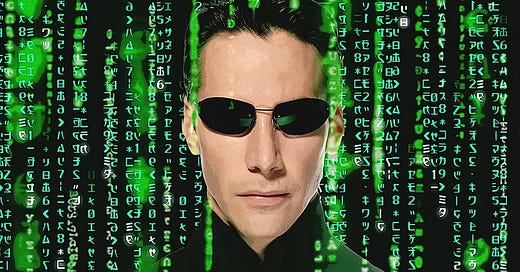

I cannot say exactly the moment I “woke up.” It wasn’t quite like my old friend from Washington, D.C. It has been more a gradual awakening over the past several years, as I have left careers in law and politics to join Indigenous communities across the Episcopal Church in a Gospel of Jesus made known and made new in their midst. I intend to share the stories of that awakening here, as we wrestle with the realities of what Willie James Jennings calls “the heart of Whiteness” in The Christian Imagination: the Theology and Origins of Race (244). But, as I reflect on my upbringing – on the stories I was told about myself, my family, and the world we inhabit – I find myself relating, more and more to Neo in the 1999 Sci-Fi classic, The Matrix. I find myself at a moment in my life when, like Neo, I have been unplugged from the systems of power and privilege and perception I have called home for the last 43 years. And, plucked from the Matrix, I hear the words “Welcome to the real world” ringing in my ears. What is this world I find myself in? A world in which everything I have known and believed to be true – about myself, my family, and the ideas and institutions I hold dear – has been fabricated for one end: the protection, preservation, and propagation of Whiteness.

As Jennings notes, “The social and moral landscape belongs to the White characters” (246). We all know this is true. So, what does it mean for me, an Episcopal priest to acknowledge that the ideas and institutions of my church – where 90% of membership is White – were shaped by and for White men to protect the power, privilege, and prosperity of White men? And how are those ideas and institutions of Whiteness (in)congruent with the teachings of a first-century Palestinian Jew who most assuredly was not White? We are wrestling questions like these on the Episcopal Church’s Truth-telling, Reckoning, and Healing Commission on Indigenous Residential Boarding Schools. Serving on this Commission, I am learning the extent to which the church has profited off Indigenous lands and bodies through its role it crafting and implementing federal policy for children removal through residential boarding schools. Of course, there are some – particularly those in positions of power and privilege – who resist these truth-telling efforts. But, make no mistake, that old guard is being left behind.

The time for platitudes about truth-telling and repair are long over. We can no longer be content with passaging a resolution. Too many of us stop there and congratulate ourselves with assurances of “woke-ness.” The time has come for action. We recognize now that for too long we have been blinded to the truth. We are rejecting the blue pill of complacency for the red pill of truth. And, wide awake, we plunge into the rabbit-hole of Whiteness.

I hope you will join us on this journey of awakening.

Well, Joe, I believe you have a long way to go to reach understanding in this context! I can recommend some material for you to read but you need to let me know if you are open as what I might share might be salt in the wounds of whiteness. I was asked by Bishop John Tarrent to lead the study and education of racism in the Diocese of South Dakota. I truthfully say that the diocese does not want to learn or understand the issue for fear that there will be a great restitution to be paid that will cost them what they took in the first place. In the two years of our journey we were invited to one Church to present what we learned and to seek support! That one Church was St. Paul's in Vermillion SD. No one else seemed interested, which didn't surprise me one bit. In my mind the Diocese of SD live a sham spiritual life, and I am sad about that given that my Brother served a Bishop for 15 years. At one time he took a sabbatical of three months and the vestry changed the locks on the church and his office. That should tell you a lot about where the diocese is in its thinking.

Tell me where I can find out more abt the indigenous Justice Roundtable. From this thread I learn that it’s 3rd Tuesdays at 2.