Digging in the Dirt

awakening hope of redemption amidst the lies we tell ourselves about ourselves

When I was studying religion in college, Post-Modernism was all the rage. We all grappled with the “truth behind the truth,” challenging the conventional wisdom of a universal truth, recognizing that truth is often a construct of institutional power. For some, the idea of truth as a social construct that reinforces systems of power felt threatening to the bedrock of all knowledge and belief; for others – me included – it was a liberating invitation to dig in the dirt of well-worn doctrine to mine eternal truths that hold the promise of redemption.

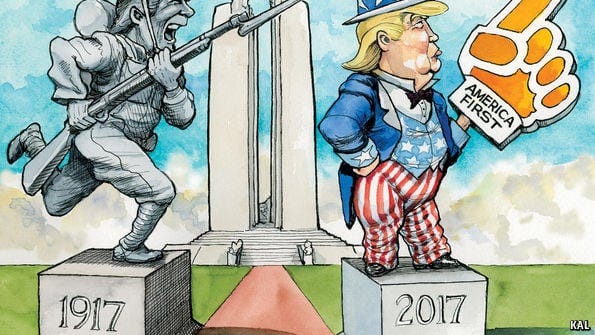

This image of digging in the dirt resonates lately as I think on all the ways the myth of American Exceptionalism is being exposed in real time, today. Despite all the political hype around a new “Golden Age” of American Exceptionalism, United States trade policy has cratered international markets, as a global trade war with China looms and American allies are increasingly alienated, even as our closest neighbor and ally, Canada, takes an increasingly hostile position to the United States, with the Canadian Prime Minister telling the world, “It’s clear the US is no longer a reliable partner.”

Have we ever been a reliable partner? Or is that myth of America as the international Boy Scout amongst the international sandbox bullies beginning to crumble? Has the United States ever put the interests of its friends and allies ahead of its own interest, or have power and profits always driven our foreign and domestic policy? As the facade cracks and falls away, I am reminded that, as has been said before, we get the leaders we deserve. Or as I wrote in this Substack after the 2024 election:

perhaps Donald Trump is actually an embodiment of American policies – foreign and domestic – over almost 250 years. He is what our Indigenous siblings and others from the global majority see when they look at the United States … a real estate tycoon, turned casino boss, turned reality TV star, turned politician, turned convicted felon.

But is there any promise of redemption?

Digging in the dirt of my own family myths and legends – seeking the truth behind the truth of my family’s long-told, never contested “exceptionalism” – I have wrestled that question almost daily, as I have often in this Substack. The legacy of the Hill family name (my grandmother’s side of the family) was ingrained in my imagination from a young age. From local lore surrounding my great-great grandfather Luther Leonidas Hill’s successful suture of the human heart (not quite as family legend boasts, which I have written about here), to the fame of his son, my great-grandfather and namesake, Senator Joseph Lister Hill, whose legacy I carried on in my own political career – being sworn into office on the same family Bible as him – I carried my families exceptionalism like an albatross, as I have written about here.

That is, until I uncovered the truth.

In November of 2020, I was sorting papers in my grandfather’s study. My grandfather and grandmother both had died within a week of each other during COVID, and I was home from seminary to bury them and begin the work of untangling their finances to probate their estate as executor. On the top shelf on my grandfather’s bookcase, I found an old metal lockbox. Prying it open with a pocketknife, I found stacks of old pictures, decaying letters, fading newspaper clippings, and, to my surprise, some old deeds. One caught my eye. A deed dated 1877, from the Senator’s grandfather, Rev. Luther Leonidas Hill, Sr. The deed conveys “A plantation of about 2,400 acres, about 16 miles from Montgomery, known as the Jones Place” to a William Wallace Hill, Rev. Hill’s nine-year-old son. Rev. Hill, a circuit-riding Methodist minister was presumably selling this property to his minor son to protect it from creditors in the post-Civil War South. I have come to learn, this particularly plantation was my family’s second one, the original being a much larger plantation 98 to the West in Hale County, Alabama, near Greensboro.

Breaking that down: A second plantation. Sold to a minor child to protect it from post-war creditors. By my Methodist minister great-great-great grandfather. This extra plantation, closer to the capital, may have been more of a “town house” for the family. But, at 2,400 acres, it was no small operation. In fact, this plantation was between three and five times the size of the average Alabama plantation. By comparison, this plantation was about half the size of Thomas Jefferson’s plantation, Monticello, which interned 400 enslaved persons. By most counts, southern plantations had one enslaved person for every 10 acres of improved land. With those estimates, there were likely 250 or more enslaved people on my great-great-great grandfather’s second plantation. Those enslaved persons would have produced about $100,000 per year in 1850, which amounts to $28,500,000 in today’s dollars.

$28.5 million dollars. A year.

In an instant I knew for certain what I had long wondered: the truth about my family’s privilege and prosperity was that it had been built on the backs of stolen people plowing stolen land, forced to labor at the end of a lash, or in some cases a shotgun. Laboring over land that, we since found out, was stolen from my children’s great-great grandmother’s people after they were force-marched to Oklahoma. In that moment, the storied exceptionalism of my family name cracked and crumbled.

Hillwood, my beloved childhood neighborhood? Named for the wooded part of the plantation developed in the early 60’s, known then as “Hill’s woods.” Silver Lane, the shady street my friends and I used to ride our bikes down? The old dirt road at the end of which, it was said, was buried the family silver when Wilson’s raiders marched through Montgomery, burning the old capital. Hill Hall, the cafeteria of my childhood school, where I performed many elementary school plays? Named for my family who donated the land and money to build the segregation academy me and all my siblings attended. Where streets and buildings and neighborhoods bearing my family’s names were once a source of pride, in that moment, they began to bear the full weight of the blood-soaked land that built my family’s name.

In that moment, the landscape of my childhood shifted. And, in the moments since, as I have reflected on these truths behind the so-called exceptionalism that afforded me opportunities funded by generational wealth built on the backs of stolen people working stolen land, the narrative has shifted. I now see how those many privileges I took for granted growing up came at a great cost – just not a cost born by me or my family.

Is there a promise of redemption in the rubble of the lies we tell ourselves about ourselves? I haven’t found it yet. But I am now awake to that possibility. I can be complicit no more. And I will keep sifting the dirt.

Your post set me to thinking - no doubt part of your plan.

Sometime early in grade school, I became aware of the Civil War. (It started with getting a toy "Johnny Reb Cannon" for Christmas in 1962.) That awareness grew into a greater understanding of the cause of the war and slavery. The child in me scorned the slavers and pitied the slaves. The child in me was looking for good guys and bad guys. I'd always assumed that the Union, the North, were the good guys and the Confederacy - Well, you know.

Hollywood did its bit, making movies out of the works of Mark Twain. Of course, there was "Gone With the Wind." And then there was "Roots."

In my college years, I began to understand how white slave-holders largely inherited a way of life. "Understanding" didn't mean agreement. Human beings are afraid of uncertainty and that fear is what, IMHO, prevented so many from taking action against what they knew was wrong. Perhaps it kept them from even recognizing it was wrong. "Momma and Daddy wouldn't have done it if it was wrong."

I often wondered how the great-great-great. . . . grandkids of "The Old South" saw their ancestors and saw themselves. Part of me would like to see them take the position that Germany has taken regarding the Nazis and the Holocaust. I suspect they just can't bear the shame.

A lifetime of mulling it over hasn't led me to accept the wrongs of the past. It's helped me forgive them, but I am still working on it.

Hello Joe! I have thought long and hard about this article. I have some troubling things I would like to ask. First let me state that when Liz and I were at Swanee in Tn, I notice that there were many Legal folks who were studying to be priests. I had always found that strange, but less so as I have aged. Meaning no disrespect, for a man of the cloth, as they say, you seem to be wealthy enough to travel freely, to New Mexico, to Virginia for baseball games and from state to state fairly often and freely. Wealth seems to be no problem. You also write about your Native brothers and sisters, which I assume is a priestly relationship, although you have stated that your family has native blood. So, I hope you can understand my confusion about what your article stated. I am judging that what happened in South Dakota taught you not to show too much support for the Native people which can be a bad thing! I admit that I do not know the whole story but have tried to put together bits and pieces. I am glad you are coming to grips with the privilege you have lived with but is what is happening now out of guilt, or remorse? Your writings leave me with many more questions and thoughts about what goes on in Rev. Hubbard's mind! I hope to find some enlightenment at some point. Peace